Walker Report on the Nooksack River

Walker Report on the Nooksack River

Walker Report on the Nooksack River

A 1960 report (1) authored by Washington’s Murray G. Walker, then Supervisor, Division of Water Resources, Washington Department of Water Resources (predecessor of today’s Department of Ecology) specifically identified the hydrologic condition and development potential of dam sites on the Nooksack River. We are now watching environmental and fishery recovery by removing dams placed on rivers before then (Elwah, Klamath). Hydropower had been the thing during the productive fervor of economic development in the early and middle decades of the previous century. Somewhat sidelined by enthusiasm for nuclear power, hydropower also proved detrimental to fishery. It is interesting, in retrospect, to consider the enthusiastic report of hydropower possibilities on the Nooksack done under the auspices of the late Albert D. Rosellini, Washington’s governor from 1957 to1965.

The Report first explained that it was intended to “provide background material for planning the ultimate development of the waters in this area.”

“The quantity and quality of water within the Nooksack River Basin is adequate to meet the area’s municipal, industrial, agricultural, and domestic needs for many years to come. With a planned and orderly development, the basin has a water resource potential at least tenfold the present known demand. The Nooksack River system contains adequate dam and reservoir sites with capacities for 100 percent flood control and development of 123,200 kilowatts of firm power. These figures represent single purpose evaluations of each storage site and would necessarily require some refinement for multiple-purpose projects. Further study of each site will be required to determine the extent to which multiple uses would be compatible.”

Although the report is outdated as to its original purpose, it is valuable as a model of organization that could be utilized by the WRIA 1 Adjudication Court in the judicial proceeding already underway in Whatcom County Superior Court. Any water competition problem must begin with a determination of “total water supply available” (TWSA).

Walker Report on the Nooksack River

Director Walker’s report, for example, stated that the total mean annual water budget of the Nooksack River at Lynden to be 2,540,000 acre-feet. He reported the amount that had by then been appropriated, only 282, 400 acre-feet leaving 2,257,600 acre feet available for development. (2)

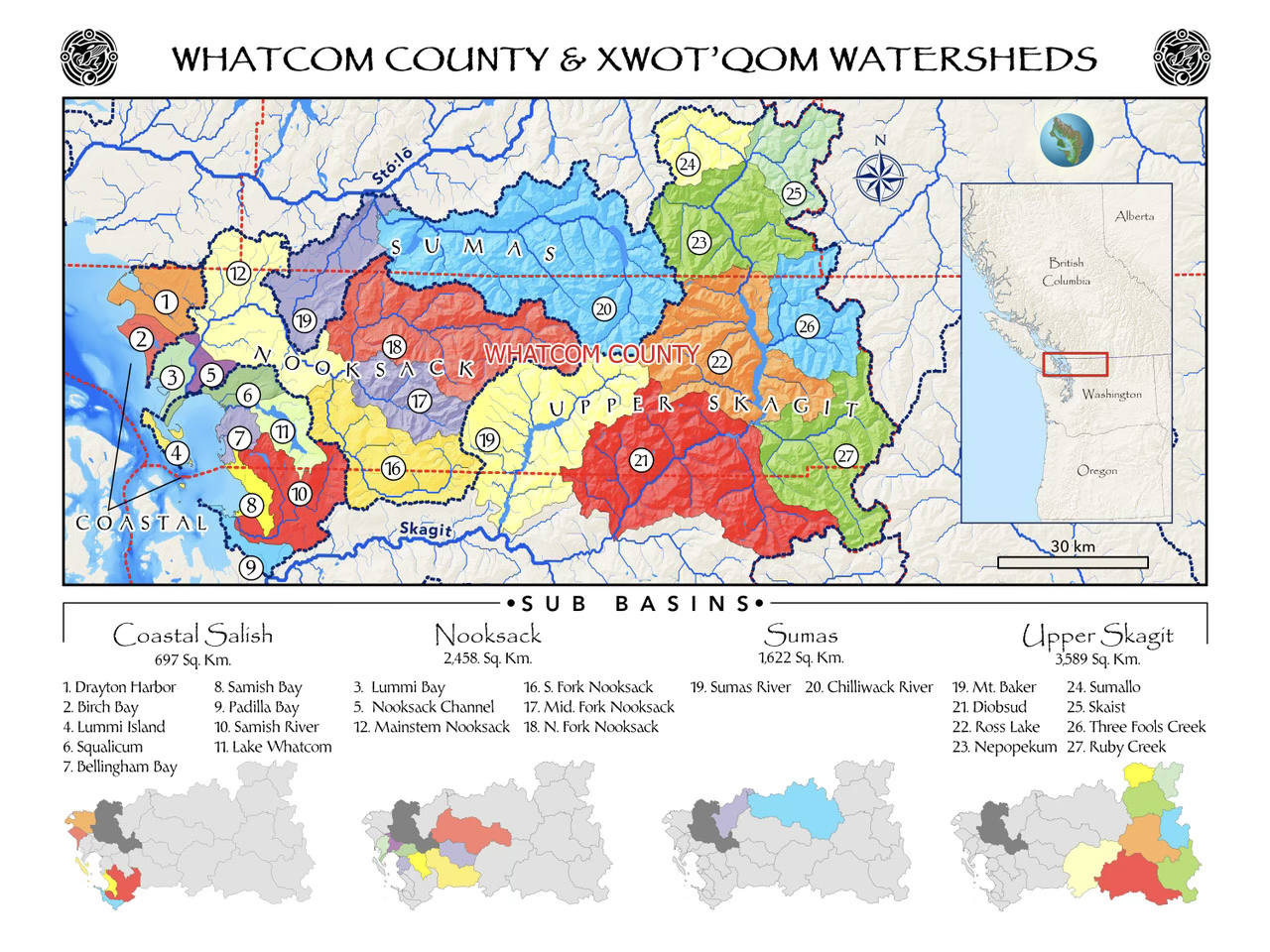

The report is also helpful in segregating the larger problem into “drainage basins, each with its own measured consumptive and non-consumptive use. These basins can be re-used, as the topography has not changed.

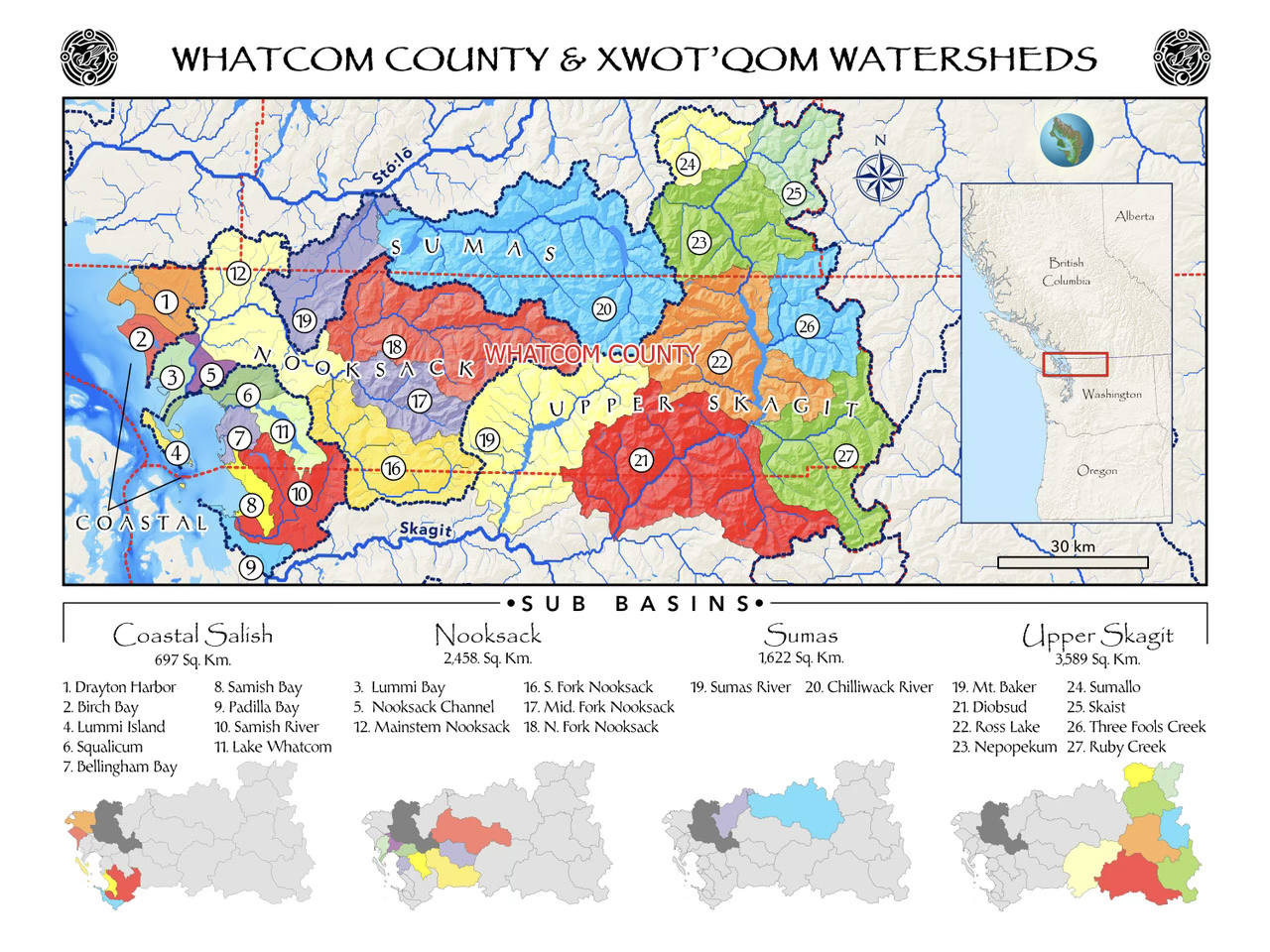

Fortunately, drainage sub-basins have now been digitized, permitting precise definition of their geographic boundaries, hydraulic relationship to underground water supplies and interaction with gaining and losing segments of surface water systems.

Walker Report on the Nooksack River

Contemporary TWSA should not be difficult to determine. DOE and USGA have, together, established a comprehensive gaging system with gages throughout the Nooksack River system at all points where the water leaves one sub-basin and enters another. This will be much more difficult with groundwater, of course, as underground aquifers are much less characterized.

TWSA has likely changed dramatically since 1960. The impact of climate change on water supply is dramatic throughout the American West. Compliance with the Department of Ecology’s 1985 “instream flow” requirement is declining rapidly. In 1960, “Approximately 90 percent of the total mean annual runoff of the Nooksack River system discharges into Georgia Strait without being put to beneficial use. Peak flows occur during water-surplus periods, October to May.” (5) What is the total mean annual runoff percentage now?

Walker Report on the Nooksack River

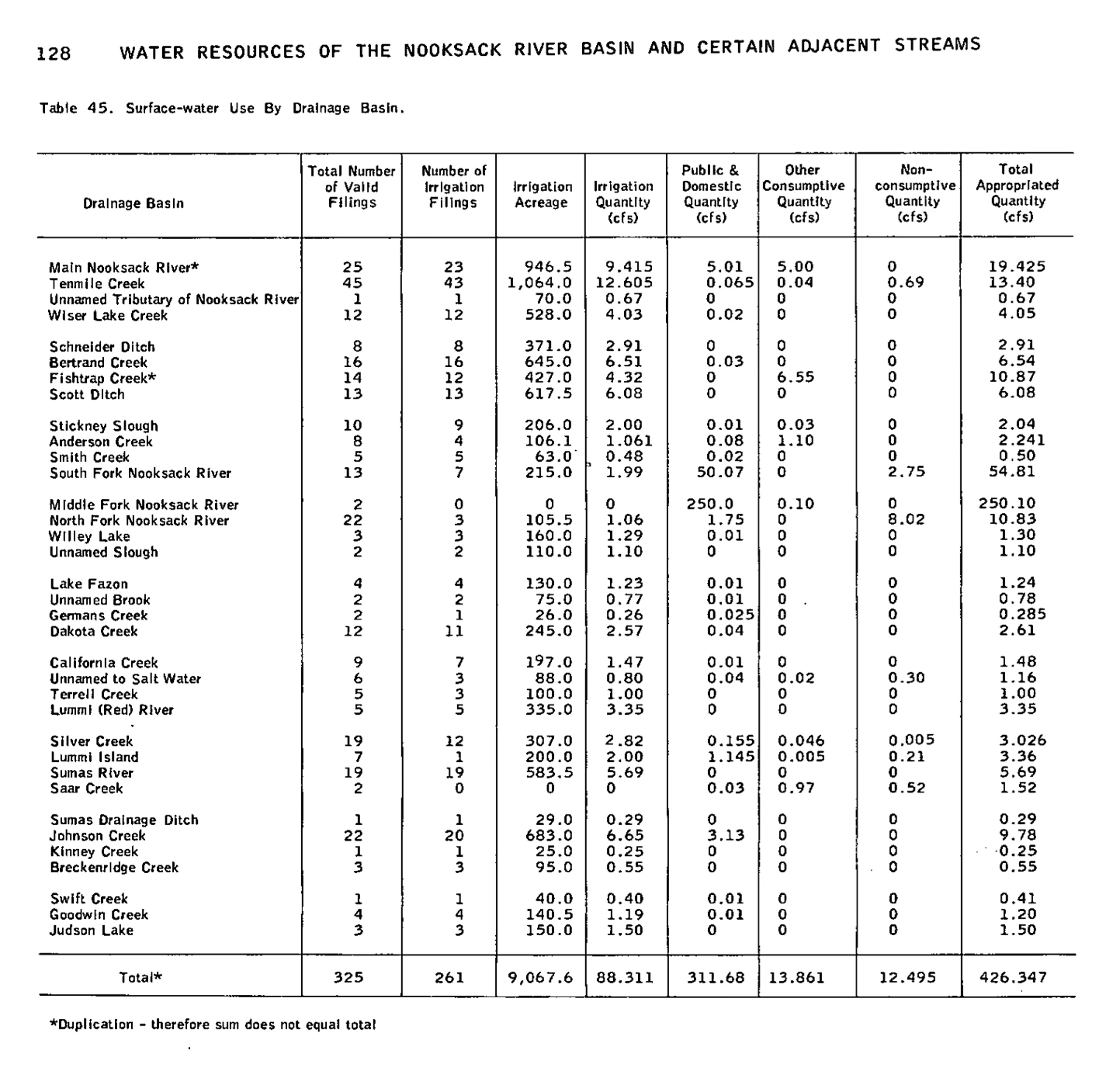

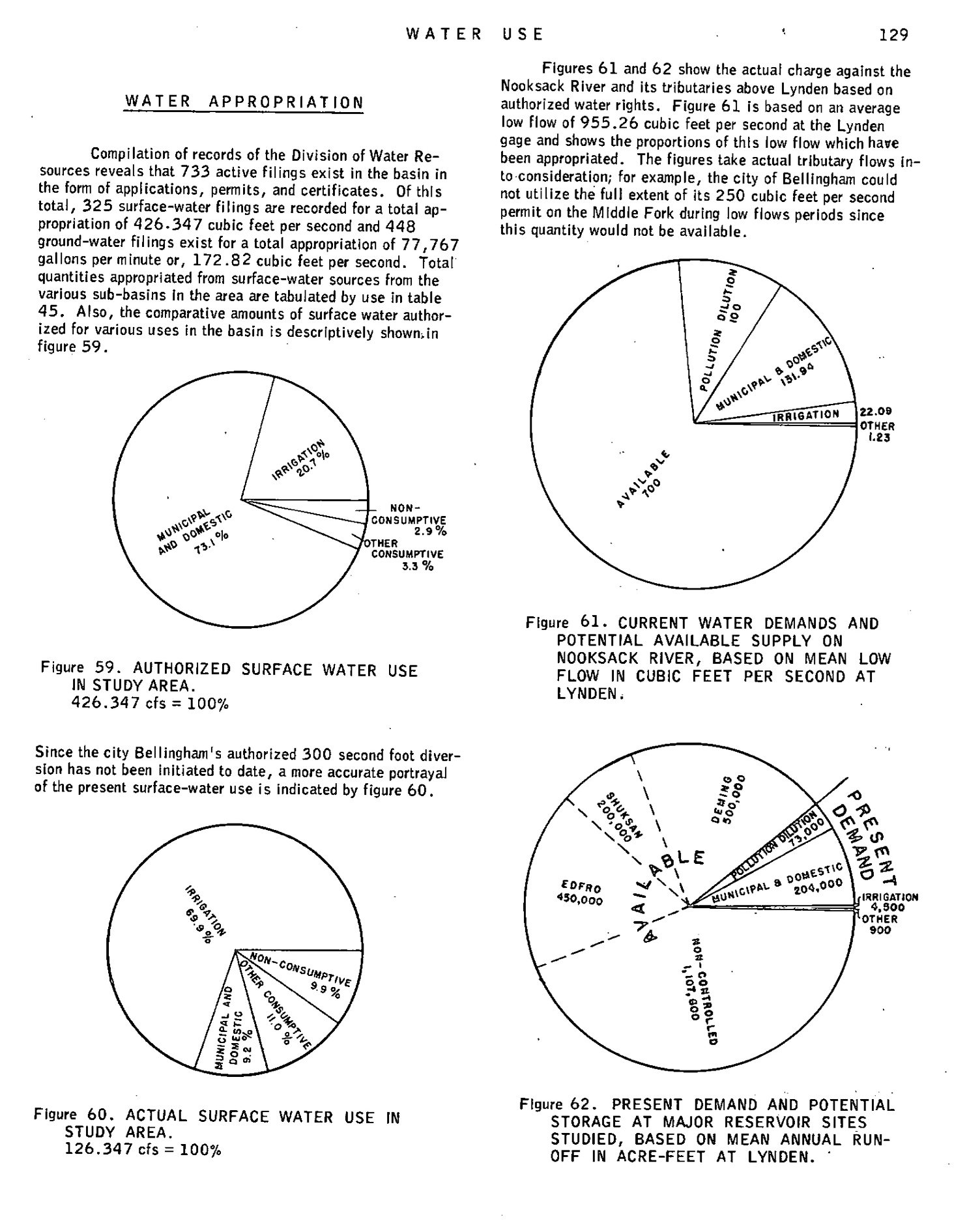

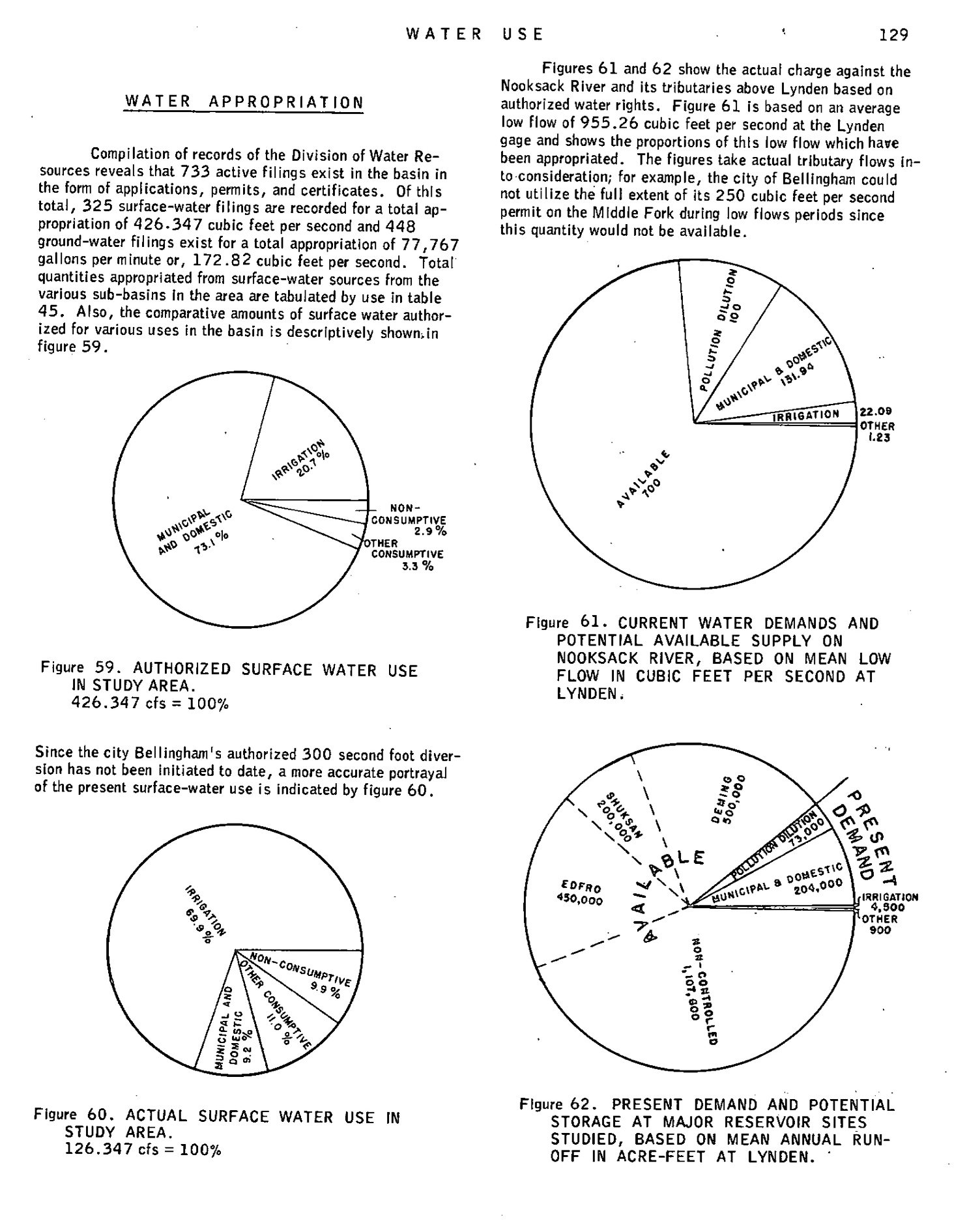

The next task is estimating the current consumptive use. Back in 1960, consumptive use was much smaller. Director Walker’s pie-charts graphically demonstrated consumptive use of the Nooksack river system back then. In 1960, there were 325 surface water filings to appropriate 426.347 cfs and 448 ground-water filings to appropriate 172.82 cubic feet per second.

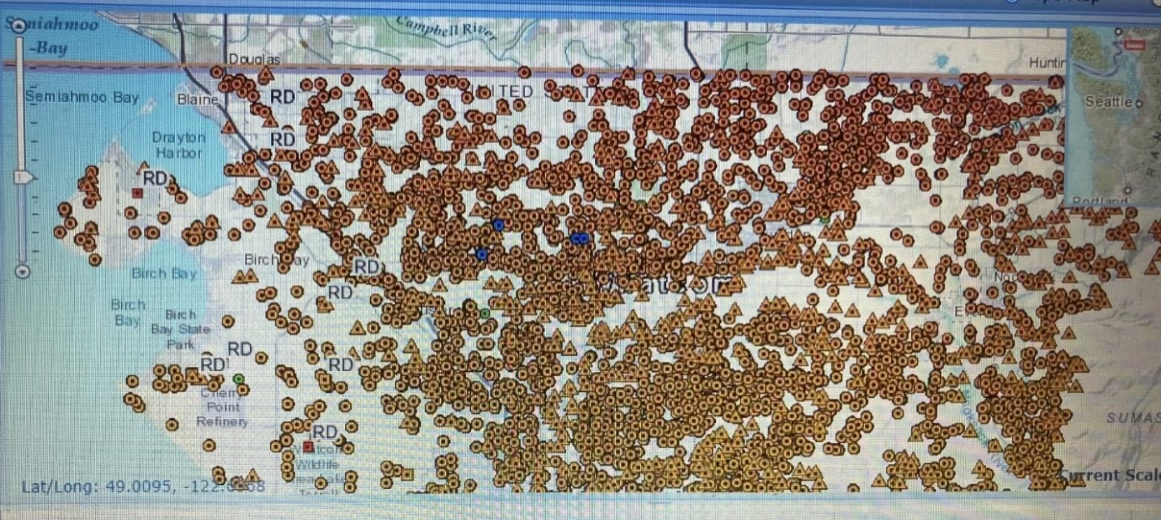

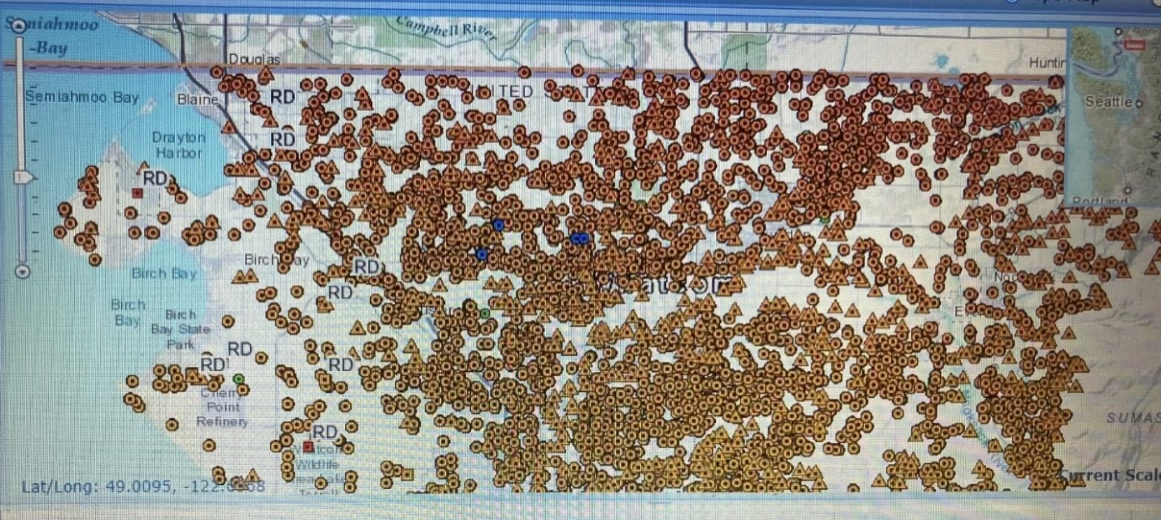

Fortunately, the Department of Ecology’s Water Resources Web Map (6) digitally locates all the surface and groundwater consumptive users within WRIA 1, permitting their distribution into the same sub-basins.

A lot has changed since 1960. Ecology claims that there are now some 30,000 claimants. A quick check of the Department of Ecology’s searchable list of known water rights indicates that there are numerous surface and groundwater consumptive uses now existing within reasonable proximity of surface creeks, streams and rivers within WRIA 1. Hydraulic conductivity likely exists between at least some groundwater wells and gaining or losing reaches of surface creeks, streams and rivers within WRIA 1.

Quantifying TWSA, claims of consumptive use, and percent of flow which currently reaches the Strait of Georgia is the easy part. The difficult part is adjudicating the competition between consumptive uses and instream flows as required by Washington statutes. The latter implicate recovery of the salmon populations that use the Nooksack’s spawning grounds, the longevity of the endangered Southern Resident Orca who eat them, the right to fishery habitat enjoyed by tribal communities, and the aesthetic pleasure enjoyed by the public to whom Washington’s statute says the water “belongs.”

In 1971, the Washington legislature charged adjudication courts with the responsibility to adjudicate “all rights to the use of water, including all diversionary and instream water rights,” (8) in a manner which accomplishes the “maximum net benefit.”

Walker Report on the Nooksack River

Let’s not forget. We’ve got to recover the fishery. The TWSA in the 50s and 60s were during the heyday of the salmon fishery. I can remember standing on Anacortes’ pier #1 in the late 50’s, as fishermen with colorful hats and tired, begrudging smiles hauled salmon ashore, those then piling and writhing to my knees. I remember the stinking carcasses of spawned-out salmon near ephemeral streams in my grandma’s cow pasture near the Samish river. The “instream flow rule” doesn’t work.

It’s not just about us versus them, or senior versus junior. It’s about sharing the resources for the maximum net benefit. This is the hard part. It takes compromise and caring about the public good. Fortunately, RCW 90.03.160 (2) authorizes the Court to appoint a referee, sometimes called a commissioner, magistrate, or special master, to assist the Court. A referee could begin with sorting out conflicts, including those between ground and surface water, in smaller bits: perhaps in those individual rivers and streams listed in Director Walker’s 1960 Report or in hydrographic districts, watersheds or “sub-basins.” The master could consider the impact of climate change, including reduced water supply from Mt. Baker’s glaciers, changes in temperature and precipitation.

The peace and beauty of the riverine system, which hasn’t changed since the 50’s, is too valuable to forfeit. Rivers have a right to reach the sea. Development of the Nooksack feels absurd. The question of reasonable habitat recovery standards and reasonable withdrawals of water from the Nooksack and its tributaries’ mean river flow will now hopefully be addressed in the pending WRIA 1 water adjudication by judicial consideration of the “maximum net benefit” approach required by the 1971 Water Policy Act (9) and its 1979 reiteration. (10)And hopefully, the quantitative evaluation of the natural system will be supported by actual quantification of existing conditions at least as competent as that Governor Rosellini demanded back in 1960.

- Washington Department of Conservation, Division of Water Resources, “Water Resources of the Nooksack River Basin and Certain Adjacent Streams,” Water Supply Bulletin No. 12, (1960). https://apps.ecology.wa.gov/publications/SummaryPages/WSB12.htm

- Walker then estimated the remaining supply capacities that might be available: “Major storage sites that have been studied have capacities for salvaging 1,150,000 acre-feet of this total, leaving 1,107,600 acre-feet of unsalvable water.” Washington Department of Conservation, Division of Water Resources, “Water Resources of the Nooksack River Basin and Certain Adjacent Streams,” Water Supply Bulletin No. 12, (1960), p.

-

“Water rights permits and certificates place a low-flow demand of 255.26 cubit feet per second or 26.7 percent of the average low flow of the Nooksack River as gaged at Lynden. This figure includes 100 cubic feet per second for pollution abatement and fish passage purposes. There remain in the stream available for appropriation 700 cubic feet per second or approximately three times the present demand of record.”

- Image courtesy of the Salish Sea Foundation

-

Washington Department of Conservation, Division of Water Resources, “Water Resources of the Nooksack River Basin and Certain Adjacent Streams,” Water Supply Bulletin No. 12, (1960).

-

Washington State Department of Ecology “Water Rights Search, Water Resources Web Map. https://ecology.wa.gov/regulations-permits/guidance-technical-assistance/water-rights-search

-

Orange dots indicate location of consumptive use claims documented in DOE records. Search of this database produces copies of the documents supporting these claims. J.H, Davenport photograph of computer screens, 8/20/24.

-

Proceedings conducted pursuant to RCW90.03.110 through 90.03.240 and 90.44.220. See RCW 90.03.245.

-

“Allocation of waters among potential uses and users shall be based generally on the securing of the maximum net benefits for the people of the state. Maximum net benefits shall constitute total benefits less costs including opportunities lost.” RCW 90.54.020 (2).

-

“It is the policy of the state to promote the use of the public waters in a fashion which provides for obtaining maximum net benefits arising from both diversionary uses of the state's public waters and the retention of waters within streams and lakes in sufficient quantity and quality to protect instream and natural values and rights.” RCW 90.03.005.

5 Comments, most recent 4 weeks ago